It’s The Banner Saga month in Game Music Hub! This article continues a four-week coverage on Austin Wintory’s stunning trilogy of scores for the tactical, turn-based RPG series of games. Click here to read last week’s article.

One of the things that attracts me to game, film and TV scores that other types of music don’t really offer is the idea of it supporting a story portrayed on the screen. The thought of representing characters, places, relationships, or esoteric concepts through music. No words, no lyrics, just melodies, instrumentation and development. Musical constructs evolving over time to complement ever-shifting dynamics in both character and plot, taking the score in interesting directions and helping provoke that palpable rush of emotions that emanate from a well-told story.

Hearing a piece of music against film or gameplay is a special kind of joy to behold. There’s nothing quite like hearing a musical gesture at exactly the right moment in a film, making you feel something that the images and sounds alone wouldn’t have been able to do. With games it’s even more fascinating because of their interactive nature. When done well, hearing the score react to you as the game unfolds can be a powerful experience.

Of course, a composer can only tell a traditional musical narrative if the project they’re scoring tells a story of its own, and with games coming in literally all shapes and sizes, that’s not always the case. And mind you, I’m not implying that a score for a game with little to no story is lesser than one for a story-based game. Just look at things like the Minecraft expansions, the Civilization games, or platformers like Cuphead, LittleBigPlanet or the Mario franchise. All of them filled with great music written for games that are mostly all about gameplay.

But every now and again comes a story-based game that really benefits from a fully-thematic, sprawling score as detailed and intricate as the narrative it’s supporting. And I couldn’t think of a better example of this than The Banner Saga trilogy. Stoic’s massive epic about choices and consequences, unimaginable loss, the burden of leadership, prejudice and love weaves the tales of dozens of richly-drawn characters as complicated and messy as the crumbling world they live in.

The trilogy’s unflinching story is the perfect musical canvas for a composer and, thankfully, Austin Wintory knew just what to do with his scores for the games. The music is heavily inspired by Nordic culture (as the world of the games are) and concert pieces for wind orchestras, and the creative combination of the two gives the trilogy an unmistakable signature sound.

Alongside the instrumental palette, Wintory provides the score with a handful of thematic ideas for a number of characters and concepts within the story. He goes on to do many interesting things with them, bending and twisting them as the characters evolve across the trilogy, creating an intricate tapestry of musical storytelling that is actually not that common (to this degree) in the world of gaming.

And it’s this intricacy, this level of depth in the musical narrative that prompted me to write about it. I’ve actually been wanting to write about this side of the games for years, even before this site was a reality, but I’ve always known it’d be a lengthy and laborious endeavor. And indeed, this turned out so much bigger in scope than I could have imagined, so much so that I had to split it in three parts. This is just the first one, where I’ll cover the entirety of the first game.

DISCLAIMER: The rest of the article contains MAJOR spoilers for The Banner Saga.

The Banner Saga trilogy takes place in a Viking-inspired world inhabited by humans and giant horned-humanoids called the Varl, who waged war against an ancient race of stone beings called the Dredge decades before the start of the first game, eventually banishing them to the lands deep into the north. There’s a lengthy period of tenuous peace between varl and humans until, one day, the sun stops moving in the sky. Soon after, Dredge start pouring back into the land and an incresingly bizarre series of events makes it clear that the world is ending. The game is told from different perspectives, with the characters of human Rook, varl leader Hakon and varl tax collector Ubin serving as our main POVs into the story.

As the first game within the trilogy, The Banner Saga does probably the most amount of heavy-lifting when it comes to the introduction of themes. The bulk of the thematic ideas for the whole trilogy have their start here, some already fully formed, and some as seeds that will blossom in the subsequent games.

The first of them is the Main Theme, which prominently plays over the menu screens for the three games (found on the albums as We Will Not Be Forgotten, An Oath, Until the End and Steps, Into Memory). It’s a long-lined, solemn, hymn-like melody, typically performed on brass. While it doesn’t represent anything specific within the story, it is the connective tissue that ties together the three scores, and it also serves as the basis for one other thematic idea that will be discussed below.

The main theme is more often hinted at rather than outright stated, being introduced in-game during the opening cutscene, scored by How Did It Come to This? from the first album, at first detached and subdued as Ubin and his caravan arrive at the port city of Strand, then more menacingly as they climb up to the main hall of the city to stop a riot.

These two statements within the track are pretty representative of how the main theme is quoted by Wintory throughout the score, such as preceding the giant crescendo at 0:04 in the track Embers in the Wind as Hakon’s caravan arrives at the varl capital of Grofheim to find it torched to the ground several chapters later, at the very end (1:35) of Three Days to Cross, which plays during the final push of Rook’s caravan towards Einartoft in Chapter 4, or not long after during the second half of Walls No Man Has Seen as the caravan finally arrives at that varl city-fortress.

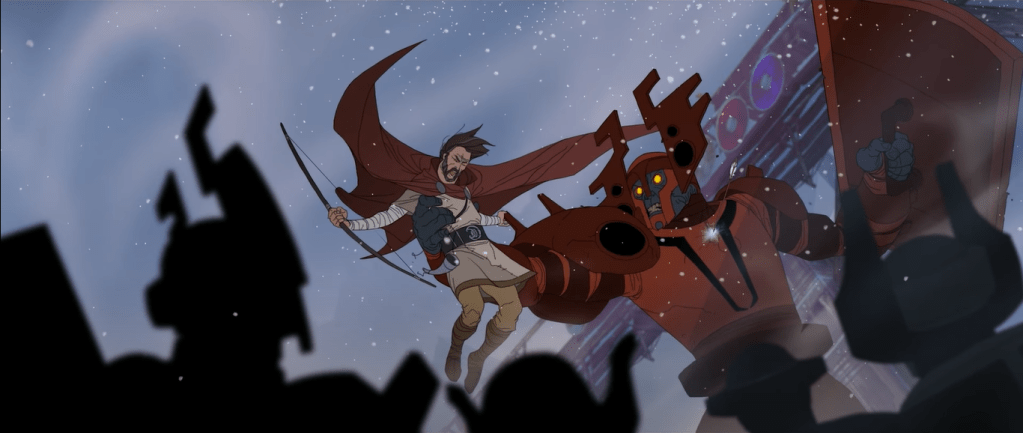

And while we’re speaking of Rook, another very important musical construct from the score is the Hero Motif, which represents the relationship between Rook and his daughter Alette during the first game. It’s a series of four-note phrases that follow a stepwise progression, versatile enough to be nimble and energetic during the action sequences, but still heartfelt and fragile during the more intimate moments.

It’s introduced with the characters’s first appearance at the start of Chapter 2, as Rook and Alette are spooked by a Dredge warrior in the woods near Skogr. Cut with a Keen-Edged Sword scores these early moments of the fight with the Dredge. The motif’s first appearance during that track happens at the very start, at the 0:10 mark, which plays during the map transition from Hakon’s location to Rook’s. Then, later in the chapter, after Rook and his caravan have left Skogr, combat encounters against various human groups are scored by the cue starting at 1:57, with the motif blending into the larger arpeggiated violin figure.

The violin, performed by Taylor Davis, is actually an intentional choice by Wintory to represent the characters sonically. It being the rare use of a typical string instrument, the violin immediately stands out among the Scandinavian instrumentation and the wind orchestra. As such, during the first game, the violin only populates the music in the chapters with Rook as the POV character.

While the primary instrument of the Hero Motif is the violin, woodwinds occasionally take up the motif, like in the track Huddled in the Shadows as Rook and Alette ride into Skogr after the fight. Huddled in the Shadows is also important because it gives us our first hint towards a very important theme to be introduced much later into the game.

This theme is one that lurks in the background for much of the first game, only occasionally gaining prominence during the second game, and eventually becoming one of the dominating themes of The Banner Saga 3.

It represents the mender Juno and her mysterious relationship with Eyvind, both found by Hakon and his caravan during Chapter 3. Its introduction happens as Hakon’s caravan walks into the destroyed Ridgehorn, scored by Thunder Before Lightning, with hesitating brass hinting at the melody at the 0:33 mark. The score comments on the importance of this moment, even if the player isn’t aware of it yet.

Juno’s Theme is actually sprung off from the main theme. One of the things that makes this one so hard to spot during the first game is precisely this similarity between the two. Notice how the two themes follow similar progressions but the intervals are somewhat inverted (the notes that go down in the main theme go up in Juno’s theme and vice versa). You could be led into thinking that Juno’s theme is merely a variation of the main theme (which it still technically is), instead of its own thematic identity representing its own thing.

But this close relationship between the two themes is very much intentional, since Juno and Eyvind are at the heart of the events throughout the three Banner Sagas. That makes this idea one of the, if not the most important theme in the entire trilogy. It’s only natural that it guards a very close relationship with the theme that represents the entire story.

However, for much of the first game, Wintory chooses to play it subtly (it makes sense, if only because Juno is absent for most of it). Like I said, this theme doesn’t really blossom until much later into the trilogy. It remains mostly absent here, gaining some small prominence during the final chapters of the game, when she herself gains prominence in the narrative.

Its most noteworthy appearance happens before that, at the start of Chapter 5, when the game chooses to shift gears and show us a conversation between Juno (who up to this point was assumed to be dead) and a giant Serpent that bursts from underground during the events on Einartoft at the end of Chapter 4.

This conversation is scored by Weary the Weight of the Sun, with the theme being prominently explored by synths (listen for the 0:06 mark) over a bed of ambience that Wintory goes on to develop during the following two games, representing the general concept of the “Darkness” that engulfs the world and is deeply connected to both the Serpent and Juno.

The main theme and hero motif form the basis for much of the narrative of the first game. However, Wintory also peppers the score with a couple of minor motifs and textures to support the conflicts throughout the game in more subtle ways.

The first of these is a general Caravan Motif that is properly introduced during the battle of Einartoft, as the combined caravans of Hakon and Rook and Alette fight off hordes of dredge coming through the bridge into the city. You can find its first appearances on the album during Strewn Across a Bridge, at the 0:58 mark (and also listen to 1:22 for how Wintory transposes the main theme to the mean tones of low woodwinds). The fanfare-ish motif forms the basis for the action in this track, and goes on to become a prominent action idea that recurs throughout the first two games.

If you pay close attention, you will hear how this fanfare is very closely connected to one specific motif in the score– the Hero Motif. While the rhythmic cadence of the melody is changed, the two motifs share similar stepwise progressions. And given that the motif is rarely stated outside of moments that involve Rook or his caravan in some way, the connection isn’t far-fetched.

A second connection between this motif and another one is more tenuous, so take it with a grain of salt– I believe this motif is tied to the main theme as well. Listen to the opening moments of No Life Goes Forever Unbroken, where you can find the seeds of the caravan motif in melody form performed by Peter Hollens, creating a striking similarity to the main theme’s melodic progression. This melody form is only sporadically used; in-game it’s actually performed on a lone trumpet during the opening text crawl that discusses the death of the gods and the stopping of the sun, and it returns to the forefront once more at the very end of the game.

A general Action Motif is hinted at during Thunder Before Lightning (2:17) and Strewn Across a Bridge (4:07) before revealing itself fully in Into Dust at 0:13, set contrapuntally against the main theme. A set of two descending notes exclusively performed on brass, it’s subtle and malleable enough to sneak its way into many action sequences, particularly during the third game. Its most prominent performances in the first game come during the climatic Of Our Bones, The Hills as both a rhythmic motif on bass trombones at 6:31 and as an exploding crescendo after an extended performance of the Caravan Motif at 7:12. Of Our Bones, The Hills as a whole will be discussed extensively in a little bit.

The final two ideas in the score are actually purely textural. I’ve already briefly mentioned one of them– it represents the concept of the “Darkness” engulfing the world. The other set of textures represent the Dredge.

The Dredge Textures are initially the sounds of didgeridoo and a prepared electric guitar being put through the wringer (from dropping objects unto the strings to being sawed in half), and its first appearance occurs in Cut with a Keen-Edged Sword as Rook and Alette fight off the Dredge in the woods. Listen for the 0:34 and you’ll hear the two main sounds that make up these textures– one a piercing didgeridoo drone and the other what sounds like the tortured scratching of an electric guitar. They immediately give the Dredge a distinctively alien, almost mechanical sound that captures their “otherness” very well. These textures feature in both subtle and obvious ways throughout the first game as the threat of the dredge grows larger and more uncontrollable.

The Darkness Textures, by comparison, are higher-pitched and much less abrasive, but no less alien and unsettling. Their only prominent appearance in the first game happens during the conversation between Juno and the Serpent. The timbre of the synth texture quoting Juno’s theme in Weary the Weight of the Sun is its most distinctive feature alongside the harp, which hints at the fuller sound that Wintory will develop for it by the time of the third game as this concept becomes more important.

Initially all themes start out scattered in their respective storylines, tied only by the main theme. Listen for the 0:36 mark in Embers in the Wind, for example, as Wintory quotes the hero motif and the main theme contrapuntally, being one of the many cues playing over the travels of Rook’s caravan.

However, as the game nears its end the storylines converge at Boersgard, the game’s final location. It’s here that Wintory subtly intertwines the themes even further. The hero motif forms the basis of the staccato woodwind and brass figures at the start of Our Heels Bleed from the Bites of Wolves before the main theme joins it at 0:23. On top of the already discussed contrapuntal statements of the main theme with the action motif, Into Dust also pits the main theme (on trombones) and Juno’s theme (on violin, since at this point in the story Eyvind travels with Rook and Alette in search of Juno) together at 1:25, making their resemblance even more evident. More interestingly, Long Past that Last Sigh features an extended performance of the hero motif atop a bed of voices humming a variation of the action motif at the 1:03 mark as Rook has to make an important decision regarding him and Alette.

The mammoth Of Our Bones, the Hills features the biggest examples of thematic interplay in the score. The track is actually made out of several battle cues for different combat scenarios that happen in the final chapters of the game, the first one from 0:20 to 2:15, then from 2:16 to 5:30, from 5:30 to 6:31, from 6:31 to 7:32, and from 7:39 to 10:18 (though this last cue is arranged specifically for the album, as it’s not heard quite like this in-game). You can hear the caravan and action motifs in some form throughout each of the cues as the combined caravans of Rook and Hakon fight their way into and then throughout Boersgard.

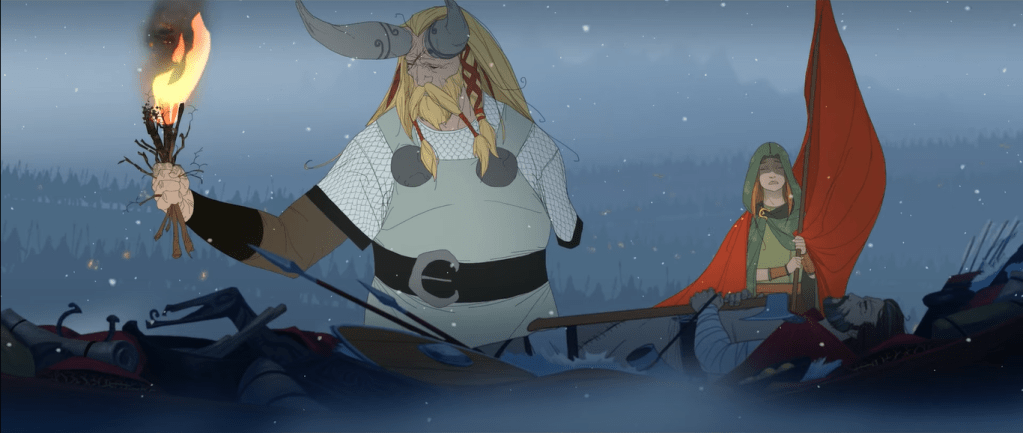

One final threat comes in the form of the immortal Dredge Sundr (a chieftain of sorts) Bellower, whom the caravans previously fought in Einartoft, and who has now rallied an army of Dredge outside the walls of Boersgard. Deeming the city too unsafe to stay on, the caravans decide their best bet is to build boats out of materials found in Boersgard and flee the city at the first opportunity.

Juno, who is eventually found by Hakon and other survivors from Einartoft and eventually reunites with Eyvind and Rook’s caravan, comes up with a plan to curse Bellower into believing they can be killed. In order for the curse to work, an arrow strong enough to pierce through their stone armor needs to be fired, Juno implying that Rook should be the one to fire it. However, when he goes to say goodbye to his daughter, she pleads to let her fire the shot. The game can end one of two ways because of this choice, although the arrow will hit and Bellower will be defeated regardless.

Should he let Alette take the shot, Bellower will kill her, leaving Rook to live with the remorse of having led her daughter to her death. Should Rook take the shot, Bellower will kill him, leaving Alette to grapple with the absence of her father, forcing her to grow up and become the new leader of the caravan. I must stress how genius of a story choice this is for how fundamentally it will change one’s experience of the rest of the trilogy.

This is why I call it the Hero Motif. It represents both Rook and Alette, not just one of them. It’s also about the relationship between the two and, after the first game, it’s about the survivor grappling with the loss of the one who didn’t. As such, the decision made at the end of this game will affect the evolution of the motif moving forward. But more on that when the time comes.

The final battle of the game against Bellower is scored by the section of 2:16-5:30 from Of Our Bones, the Hills, which is essentially three cues written for the same fight at different stages. The score is implemented into combat scenarios with fight progression as a key variable; for example, the fight will begin with a specific cue looping over it (in the final battle it’s 2:16-3:33), but the more enemies you defeat, you will trigger a different cue (in this case, first 3:33-4:31, then as the fight progresses further it triggers 4:31-5:30), all of them building in intensity until the end of the fight.

I should probably take a moment here to marvel at the level of detail in the writing of these action cues, like the aleatoric woodwind passages popping up now and again (for example, at 4:05), or the crazy percussion barrage at 5:03, or the dredge textures sneaking their way into the music. This is just stellar action music, and the score goes a long way in selling the dramatic intensity of the story, which more than compensates for the lack of more traditional elements like voice acting or proper cutscenes. Wintory manages to make this small indie game feel bigger than many AAA blockbusters.

After Rook or Alette fires the arrow, Bellower goes into a frenzy, killing the one who shot it, and triggering one final stage of the fight, as the warriors scramble to finish off the Dredge chieftain. This stage is scored by the section at 7:39-10:18. Here, Wintory whips out one final, very interesting, musical idea, gorgeously performed by Malukah. Almost like a hybrid of the hero motif and small fragments of Juno’s theme, it’s a series of rising-and-falling vocal phrases; it perfectly encapsulates the shock of Rook or Alette’s death, as well as the desperation to finish off Bellower in this final stretch of the fight.

This portion of the music works a bit differently in-game than it does on the album, with most of the elements in it being separate layers that are added over time, first starting with the vocals, then the percussion, then the trombone chords, and then the aleatoric trumpets above it; this fully formed cue continues to loop until the end of the fight. On the album, Wintory streamlines this rise in intensity and goes much further, stacking layers and layers of aleatoric trumpets, building to one giant musical explosion, after which he peels off the layers again, ending the cue with just vocals again.

After the fight, Iver (Rook’s best friend) and the surviving Rook or Alette make a private Viking-styled funeral for their lost family member. The melody form of the Caravan Motif returns one final time (performed by Peter Hollens). As the burning ship sails away (spiritually) carrying the corpse into the afterlife, the music builds towards a soaring statement of the main theme, performed by both Malukah and Peter Hollens, and accentuated by Johann Sigurdarson’s Norse vocals.

The emotional end credits song, Onward, is performed by the three main soloists of the first score, Malukah and Peter Hollens on vocals, and Taylor Davis on violin. The song is built from Juno’s theme, the first time in the trilogy that the melody is presented in its entirety. This theme will become a fundamental part of the narrative moving forward, and Austin Wintory ends the first Banner Saga reminding us of that.

This article continues with The Thematic Depth of The Banner Saga 2.

THE BANNER SAGA

Music composed, conducted and orchestrated by Austin Wintory

Co-orchestrated by Susie Seiter

Co-conducted by Jerry F. Junkin

Performed by The Dallas Winds

Featuring performances by Taylor Davis (violin), Peter Hollens (vocals), Malukah (vocals), Johann Sigurdarson (vocals), Mike Niemietz (prepared electric guitar), Randin Graves (didgeridoo), Noah Gladstone (bukkelhorn), M.B. Gordy (percussion) and Austin Wintory (accordion)

“Onward” featuring lyrics by Malukah, Icelandic translation by Davíð Þór Jónsson